What follows is an excerpt from the founder of Backstone Stephen A. Schwarzman’s Biography. Blackstone is the largest alternative investment firm in the world. This is my favorite chapter so far in this book. It is so interesting to me because Stephen describes his thinking process when he created a new company. What he was looking for, his priorities. So much insight in so little text.

Now that we were free of Lehman and could work together again, Pete and I began talking in earnest about starting something of our own. We had our first conversation at Pete’s house in East Hampton with our wives.

“I want to work with large companies again,” said Pete. Since leaving Lehman, he had started a small firm that did small deals.

“I just want to work with Pete again,” I said. I was thirty-eight, and the money I had made at Lehman had provided for my young family. By now, we had two children, Zibby and Teddy, both healthy and going to great schools. We had an apartment in the city and a house near the beach. Professionally, I had reached a point where I wanted to start my own business. I felt I had learned enough and acquired enough personal and professional resources to make a success of it. Ellen, who had seen how miserable I had been during that last year at Lehman, said, “I want Steve to be happy.”

Joan, Pete’s wife, was the creator of Sesame Street, the children’s television show. She had an objective even Big Bird could understand: “I want a helicopter.”

“Okay,” I said. “We know what everybody wants. Now, let’s go.”

Many great businesses in Silicon Valley, from Hewlett Packard to Apple, have been founded in garages. In New York, we have breakfast. In April 1985, Pete and I began meeting every day in the courtyard restaurant at the Mayfair Hotel on East Sixty-Fifth Street and Park Avenue. We were the first to arrive and the last to leave, talking for hours, reflecting on our careers and thinking of what we could do together.

Our main assets were our skill sets, our experience, and our reputations. Pete was a summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, process-oriented, analytic person. There was nothing he couldn’t figure out through method and logic. He knew everyone in New York, Washington, and corporate America and had an easy, casual way with all of them. I considered myself more instinctive, quick to read and figure people out. I could make decisions and execute fast and was now well known as an M&A specialist. Our skills and personalities were different but complementary. We were confident that we would be good partners and people would want our services. Even if most start-ups failed, we were sure ours wouldn’t.

Observing my father at Schwarzman’s and all the businesses and entrepreneurs I had advised subsequently, I had reached an important conclusion about starting any business: it’s as hard to start and run a small business as it is to start a big one. You will suffer the same toll financially and psychologically as you bludgeon it into existence. It’s hard to raise the money and to find the right people. So if you’re going to dedicate your life to a business, which is the only way it will ever work, you should choose one with the potential to be huge.

Early in my career at Lehman, I asked an older banker why it was that banks had to pay more to borrow money than similar-sized industrial companies did. “Financial institutions go broke in a day,” he told me. “It can take years for an industrial company to lose its market position and go bankrupt.” I had now seen that happen up close at Lehman—that sudden reversal of fortune, a bad trade, a bad investment that can destroy you in finance. We weren’t going to start this journey in a tiny rowboat. We wanted to build a reputation for excellence, not bravery.

From the outset, we strived to build a financial institution strong enough to survive multiple generations of owners and leadership. We did not want to be just another of those groups on Wall Street who set up a firm, make some money, fall out, and move on. We wanted to be spoken of in the same breath as the greatest names in our industry.

What we knew best was M&A work. At the time, M&A was still the purview of the big investment banks. But we believed there would be an appetite for the services of a new kind of boutique advisory firm. We had the reputation and the track record. M&A took sweat equity but didn’t require capital, and it would provide income while we figured out what else we might offer. I worried about the cyclicality of M&A and that alone it wouldn’t be enough to sustain us. If the economy sputtered, so would our business. Eventually we would want steadier sources of income. But it was a good place to start. To get big, though, and build a stable, lasting institution, we would have to do much more than that.

As we sat in the Mayfair evaluating ideas, one potential line of business kept resurfacing: leveraged buyouts, or LBOs. At Lehman, I had advised Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) and Forstmann Little, the two largest LBO firms in the world. I knew Henry Kravis and played tennis with Brian Little. Three things had struck me about their business. First, you could gather assets and earn income from recurring fees and investment profits whatever the economic climate. Second, you could really improve the companies you bought. Third, you could make a fortune.

A classic LBO works this way: An investor decides to buy a company by putting up equity, similar to the down payment on a house, and borrowing the rest, the leverage. Once acquired, the company, if public, is delisted, and its shares are taken private, the “private” in the term “private equity.” The company pays the interest on its debt from its own cash flow while the investor improves various areas of a business’s operations in an attempt to grow the company. The investor collects a management fee and eventually a share of the profits earned whenever the investment in monetized. The operational improvements that are implemented can range from greater efficiencies in manufacturing, energy utilization, and procurement; to new product lines and expansion into new markets; to upgraded technology; and even leadership development of the company’s management team. After several years, if these efforts have proved successful and the company has grown considerably, the investor can sell it for a higher price than he or she bought it, or perhaps take the company public again, earning a profit on the original equity investment. There are a lot of variations on this basic theme.

The key to all investing is using every tool at your disposal. I liked the idea of leveraged buyouts because they seemed to offer more tools than any other form of investment. First, you looked for the right asset to buy. You did your diligence by signing nondisclosure agreements with the owners and getting access to more detailed information about what you were buying. You worked with investment bankers to create a capital structure that gave you the financial flexibility to invest and survive if economic circumstances turned against you. You put in experienced operators you trusted to improve whatever you bought. And if all went well, the debt you put in place enhanced the rate of return on the value of your equity when the time came to sell.

This type of investing would be much harder than buying stocks. It would take years of effort, excellent management, hard work, and patience and require teams of skilled experts. However, if you did this successfully over and over, you could generate significant returns and develop a record the way Coach Armstrong did at Abington High School, 186–4, and also earn the trust of your investors. The returns these investments earned for investors—pension funds, academic and charitable institutions, governments and other institutions, as well as retail investors—would also have the benefit of helping to secure and grow the retirement funds of millions of teachers, firefighters, and corporate employees, among others.

Unlike M&A, LBOs didn’t require a constant stream of new clients. If we could persuade investors to put money into a fund, locked up for ten years, we then had ten years to earn management fees, improve what we bought, and turn a big profit for our investors and ourselves. If a recession hit, we could survive it and, with luck, find even more opportunities as panicked people sold good assets at low prices.

Back in 1979, I had studied the prospectus for KKR’s eye-popping buyout of Houdaille Industries, one of the first big LBOs. This deal was the Rosetta Stone of buyouts. KKR had put in just 5 percent of the cash to buy Houdaille, an industrial manufacturing conglomerate, and borrowed the rest. Leverage on that scale meant the company could grow at 5 percent, but the equity would grow at 20 to 30 percent. I had been keen to do a similar deal using Lehman’s resources, but I couldn’t muster the internal support.

Two years later, I was the banker for the legendary media and electronics company RCA when it decided it wanted to sell Gibson Greetings, then America’s third biggest greeting cards company, an asset that didn’t fit with RCA’s other businesses. We contacted seventy potential buyers. Only two were interested. One was Saxon Paper, which turned out to be a fraud. The other was Wesray, a small investment fund co-founded by William Simon, a former treasury secretary. Wesray offered $55 million for Gibson, and we set a date to close the deal. Wesray’s investors were putting in just $1 million of their own capital but assured us they would have the rest of the money by the closing date. When they didn’t, we gave them a one-month extension. Still, no money. There were no other suitors. They pleaded for one more shot. I found out later that they were trying to finance the deal by arranging to sell and then lease back Gibson’s manufacturing and warehouse buildings. That would have given them the cash they needed, but they couldn’t get it done. That, I thought, was that.

In the meantime, Gibson’s earnings started going up. Although we hadn’t yet found a qualified buyer, I recommended to Julius Koppelman, the RCA executive handling the sale, that they increase the price they were asking for Gibson. He proposed an additional $5 million. I told them that wasn’t close to reflecting Gibson’s value given its rising profits, but they wouldn’t budge: RCA was desperate to sell and wanted the deal done. They weren’t interested in getting the highest price. When RCA asked me for a fairness opinion on a $60 million sale, I refused to give one, a controversial and highly atypical stance at the time. When the deal closed six months later, Koppelman left RCA to become a consultant for Wesray. After Wesray bought Gibson, I made sure to go to Pete and Lew Glucksman to tell them what I thought of it. Wesray would make a lot of money one day, I said, and we’d be accused of incompetence. When you disagree, it’s important to get your opinions on record so you aren’t blamed later when things go wrong. Sixteen months later, Gibson went public, valued at $290 million, and Lehman was highly criticized by RCA’s investors and the press for selling it too cheaply. Wesray had made more money on a single deal than Lehman made in a year.

Gibson was widely publicized for being one of the first successful, highly profitable leveraged buyouts. It was also the perfect case study of the type of deal Pete and I hoped to do at our new firm.

The good news was that after the Gibson IPO, LBOs had Lehman’s attention. Pete, then CEO, was all in. Before his next trip to Chicago, he asked me to come up with a list of possible acquisitions. I settled on Stewart-Warner, a maker of dashboard instrument panels and the scoreboards at sports stadiums. Pete, of course, happened to know the chairman, Bennett Archambault. We met him at his men’s club, an old-school place with wood paneling and moose heads all over the walls. Pete suggested he take his company private. I walked Archambault through the process: how we could raise money to buy the stock, how we could pay the interest, enhance the value, make the company work better, what it would mean over time.

“I think you can make a lot of money personally,” Pete said to him. “And your shareholders can do well. Everyone can profit.” Archambault got it. The existing shareholders would be paid a premium for their stake. As the head of a private company, he could improve it over the long term instead of worrying about quarterly earnings to placate the stock market. And he would end up owning a lot more of the company. “There don’t seem a lot of reasons not to do it,” he said.

Back at Lehman, I rushed into action. I staffed the deal and asked Dick Beattie at the Simpson Thacher law firm to start designing a fund for Lehman to do LBOs. Dick had been counsel in the Carter administration and had since become an expert on the legal intricacies of LBOs. We were confident we could raise the $175 million to take Stewart-Warner private. Pete and I moved the deal through the Lehman vetting process and brought it to the executive committee. The executive committee turned us down.

They saw an inherent conflict. They didn’t feel we could give M&A advice to our clients while at the same time trying to buy companies our clients might be interested in. I understood the basics of their position. But I was sure that there must be a compromise that could properly address the potential conflicts. Fine, we couldn’t buy every company we wanted. But there must be a way to buy some of them. The opportunity in this business was too big to ignore.

In the years after the executive committee rejected our idea, a wave of LBO money transformed the way America bought and sold companies. More buyers had emerged, eager to buy assets they could never afford previously. Banks were developing new kinds of debt, with higher yields or novel repayment terms, to fund their acquisitions. Corporations saw the opportunity to sell businesses they no longer wanted to buyers who could do more with them. To be taken seriously as M&A specialists, we had to master this dynamic new area of finance. But the even bigger opportunity, Pete and I thought, would be to become investors ourselves.

As M&A bankers, we would be running only a service business dependent on fees. As investors, we would have a much greater share in the financial upside of our work. In private equity firms, general partners identify, execute, and manage any investments on behalf of limited partners (LPs), the investors who entrust them with their money. The general partners put their own capital up alongside the LPs, run the investment business, and tend to be rewarded in two ways. They receive a management fee, a percentage of the capital committed by investors and subsequently put to work, and a share of the profits earned from any successful investments, the “carried interest.”

The appeal of the private equity business model to a couple of entrepreneurs was that you could get to significant scale with far fewer people than you would need if you were running a purely service business. In service businesses, you need to keep adding people to grow, to take the calls and do the work. In the private equity business, the same small group of people could raise larger funds and manage ever bigger investments. You did not need hundreds of extra people to do it. Compared to most other businesses on Wall Street, private equity firms were simpler in structure, and the financial rewards were concentrated in fewer hands. But you needed skill and information to make this model work. I believed we had both and could acquire more.

The third and final way we thought about building our business was to keep challenging ourselves with an open-ended question: Why not? If we came across the right person to scale a business in a great investment class, why not? If we could apply our strengths, our network, and our resources to make that business a success, why not? Other firms, we felt, defined themselves too narrowly, limiting their ability to innovate. They were advisory firms, or investment firms, or credit firms, or real estate firms. Yet they were all pursuing financial opportunity.

Pete and I thought of the people we wanted to run these new business areas as “10 out of 10s.” We had both been judging talent long enough to know a 10 when we saw one. Eights just do the stuff you tell them. Nines are great at executing and developing good strategies. You can build a winning firm with 9s. But people who are 10s sense problems, design solutions, and take the business in new directions without being told to do so. Tens always make it rain.

We imagined that once we were in business, the 10s would come to us with ideas and ask for investment and institutional support. We’d set them up in fifty-fifty partnerships and give them the opportunity to do what they did best. We’d nurture them and learn from them in the process. Having these smart, capable 10s around would inform and improve everything we did and help us pursue opportunities we couldn’t even imagine yet. They would help feed and enrich the firm’s knowledge base, though we still had to be smart enough to process all this data and turn it into great decisions.

The culture we would need in order to attract these 10s would by necessity contain certain contradictions. We would have to have all the advantages of scale, but also the soul of a small firm where people felt free to speak their mind. We wanted to be highly disciplined advisers and investors, but not bureaucratic or so closed to new ideas that we forgot to ask, “Why not?” Above all, we wanted to retain our capacity to innovate, even as we fought the daily battles of building our new firm. If we could attract the right people and build the right culture at this three-legged business, offering M&A, LBO investments, and new business lines, all feeding us information, we could create real value for our clients, our partners, our lenders, and ourselves.

Businesses often succeed and fail based on timing. Get there too early, and customers aren’t ready. Arrive too late, and you’ll be stuck behind a long line of competitors. The moment we started Blackstone in fall 1985, we had two major tailwinds. The first was the US economy. It was in the third year of a recovery under President Reagan. Interest rates were low, and borrowing was easy. There was plenty of capital looking for investment opportunities, and the financial industry was meeting this demand with a supply of new structures and new kinds of businesses. LBOs and high-yield bonds were part of rapid changes in the credit markets. We were also seeing the emergence of hedge funds—investment vehicles with highly technical approaches to managing risk and reward in every class of assets, from currencies to stocks. The potential of all these forms of investment was just emerging and the competition was not yet fierce. It was a good time to be trying something new.

The second major tailwind was the unraveling of Wall Street. Since its founding in the late eighteenth century, the New York Stock Exchange had operated with a fixed-price commission schedule, granting a set percentage of every trade to the broker. That system ended on May 1, 1975, on the orders of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which determined it to be a form of price fixing. Under the old system, Wall Street’s brokerage firms barely had to compete and certainly hadn’t had to innovate. Now that commissions had to be negotiated, price and service mattered. Technology accelerated the process, punishing the small, high-cost brokers and rewarding those who could offer better services and lower prices at scale. In the ten years since the SEC’s rule change, the firms that succeeded grew larger and larger, while those that stood still eventually died.

This change transformed Wall Street’s culture. When I joined Lehman in 1972, it employed 550 people. When I left, Shearson-Lehman had 20,000 (when Lehman collapsed in 2008, it had 30,000). Not everyone liked being part of these giants. You lost the intimacy of knowing everyone by sight, that sense of working for a single, coherent entity. You went from being part of a nimble team to sitting inside a huge bureaucracy. As a new associate at Lehman, I had caught the eye of Lew Glucksman, who yelled at me for not sitting up straight. But that led to someone telling him I had potential and him giving me work. That can happen in a firm of 550. With 20,000 people, it’s much harder to find the good, young talent. At Lehman in the early 1970s, we had people from the CIA and the military, all kinds of different fields, who learned finance on the job. They brought a wide range of skills, perspectives, and contacts to our work. But by the mid-1980s, banks were hiring armies of MBAs who could plug in and do the work immediately. Pete and I believed that these changes to the culture at the big firms would lead to a shake-out of great people and great ideas. If they were anything like us, they would be searching for ways out. We wanted to be ready for them.

For months, we agonized over what to call ourselves. I liked “Peterson and Schwarzman,” but Pete had already set up a couple of businesses that included his name and didn’t want to use it again. He preferred something neutral so that if we added new partners, we wouldn’t have to argue about adding their names. We didn’t want to become one of those ungainly law firms with five names on the letterhead. I asked everyone I knew for suggestions. Pete’s wife, Joan, talked sense into us: “When I started my business I couldn’t think of a name. In the end, we just invented one: ‘Sesame Street.’ What a stupid name that is. Now it’s in 180 countries all over the world. If your business fails, nobody will remember your name. If your business succeeds, everyone will know it. So just pick something, get on with it, and hope you succeed enough to be known.”

Ellen’s stepfather came up with the answer. He was the chief rabbi for the Air Force and a Talmudic scholar. He proposed we draw on the English translations of our two names. The German schwarz means black. Pete’s father’s original Greek name was “Petropoulos.” Petros means stone or rock. We could be Blackstone or Blackrock. I preferred Blackstone. Pete was happy to go along.

After months of talking, we had a name and a plan to be a distinctive firm composed of three businesses: M&A, buyouts, and new business lines. Our culture would attract the best people and provide extraordinary value for our clients. We were hitting the market at the right time and had the potential to be huge.

We each put up $200,000 in capital—enough to get started, but not so much that we could be spendthrift. We took three thousand square feet at 375 Park Avenue, the Seagram building just north of Grand Central Station. The building was open, modern, and architecturally significant, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the pioneering modernist architect. It was in midtown, far from Wall Street, but near many corporate offices. It was also in the same building as the Four Seasons restaurant, a famous networking location. In 1979, Esquire magazine had described it as the birthplace of the “power lunch.” It would be easy for Pete to work his many corporate contacts. Had I used us as an exhibit in my business school thesis on the architecture of financial firms, I would have noted that we were straining for prestige.

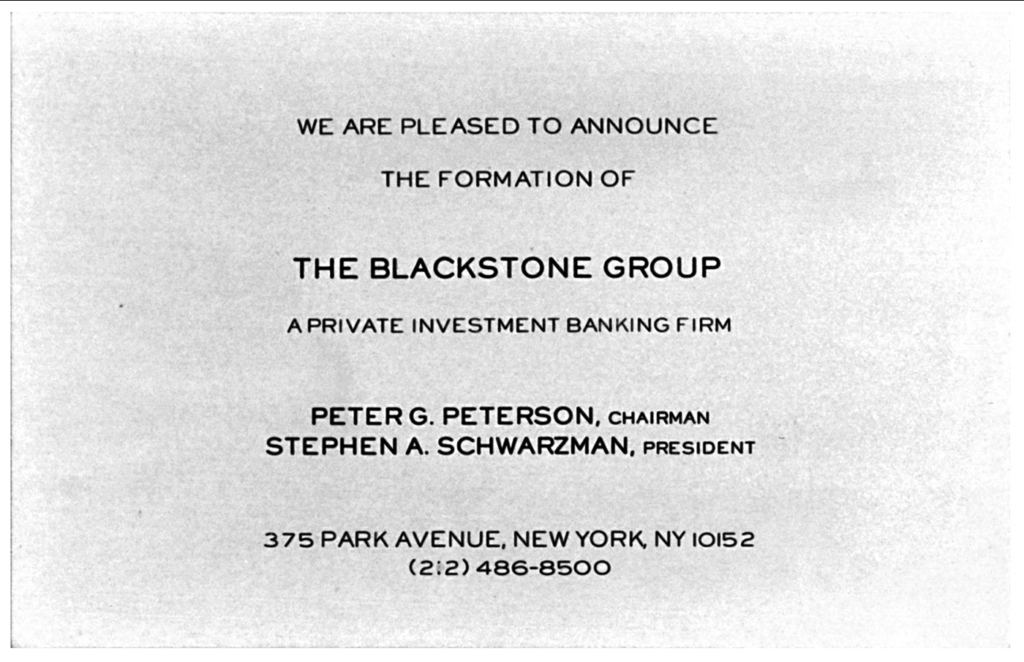

We bought some furniture, hired a secretary, and divided up our roles. Pete had been a CEO twice before and told me that he didn’t want the hassle of running a business again. He asked me to take the CEO role but with the title of president. One of my first acts was to design our logo and our business cards. I hired a design firm, had them come up with alternatives, and spent an enormous amount of time going over them. The design we chose is the one we still have: simple, black and white, clean, and respectable. I thought the time and money we spent when both were scarce were essential to getting this right. When you’re presenting yourself, the whole picture has to make sense, the entire, integrated approach that gives other people cues and clues as to who you are. The wrong aesthetics can set everything off kilter. Our business cards were an early step in establishing who we wanted to be.

On October 29, 1985, six months after we had started having our breakfasts at the Mayfair, we took out a full-page ad in the New York Times and announced ourselves to the world:

Thanks karl! Interesting book!

Glad you liked it too Dana! 😊